By: Elizabeth O'Brien

Retirement reporter

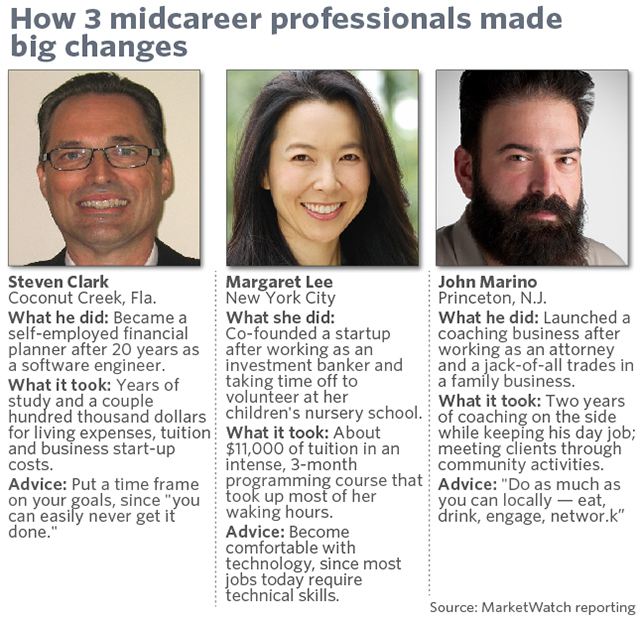

Steven Clark isn’t usually impulsive, so it wasn’t easy for him to wake up one morning and decide it would be his last day as a software engineer after 20 years.

But the stress had been mounting for years as Clark, like many successful midcareer professionals, had ended up on a management track, dealing with office politics he didn’t care for. So he quit.

“I walked away cold,” recalled Clark, now 54, of that day in 2010. “That was totally out of character.”

Clark, who now runs a financial advisory practice in Coconut Creek, Fla., made a change many dream of, ditching the cubicle to become his own boss. And experts say that for those tempted to follow him, the timing is right: Whether you want to change industries or start a business, a tightening job market — the current unemployment rate is 5.0% overall, and 3.6% for those between ages 45 to 54 — offers opportunity, they say.

“The opportunity to craft and create has never been better,” said Maggie Mistal, a life and career coach in New York City.

That doesn’t mean it’s easy. The margin of error is slimmer for workers in their 40s and 50s, who may need to continue building retirement accounts, writing tuition checks and supporting aging parents. Because of these obligations, many midlife workers can ill afford to take big pay cuts, part-time work or internships.

“You’re at a point in life where your wages matter,” said John Challenger, CEO of job outplacement firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas.

MarketWatch spoke with several midlife career changers to see how they did it. Their professional backgrounds and family circumstances varied, but they all took careful, expert-approved steps that eased and guided their transitions.

Each went into business for him or herself, rather than join an established firm. This path is by no means the only one available to midlife career changers, experts say, but it does remove one obstacle to a midcareer move: having to compete for a first job in a new industry with younger workers who can afford to work for less.

Make (and pad) a financial cushion

Clark’s decision to quit was impulsive, but he made it knowing he had a substantial savings cushion. By midcareer, Clark had a six-digit savings account, which turned into seed money he used in the coming years to pay for living expenses and the coursework he needed to prepare for the certified financial planner exam he took in 2013.

Clark’s wife worked while he studied, but she made much less than the $150,000 that he was making when he quit. The couple pared expenses, slashing the amount they spent on dinners out, cutting their cable bill to basic service and canceling their home security plan. “I was home pretty much all the time anyway,” Clark said.